On the Trail of the Cuddle Hormone

- 23 hours ago

- 2 min read

Analyses Illuminate the Pace and Mechanism of Oxytocin Release in the Brain

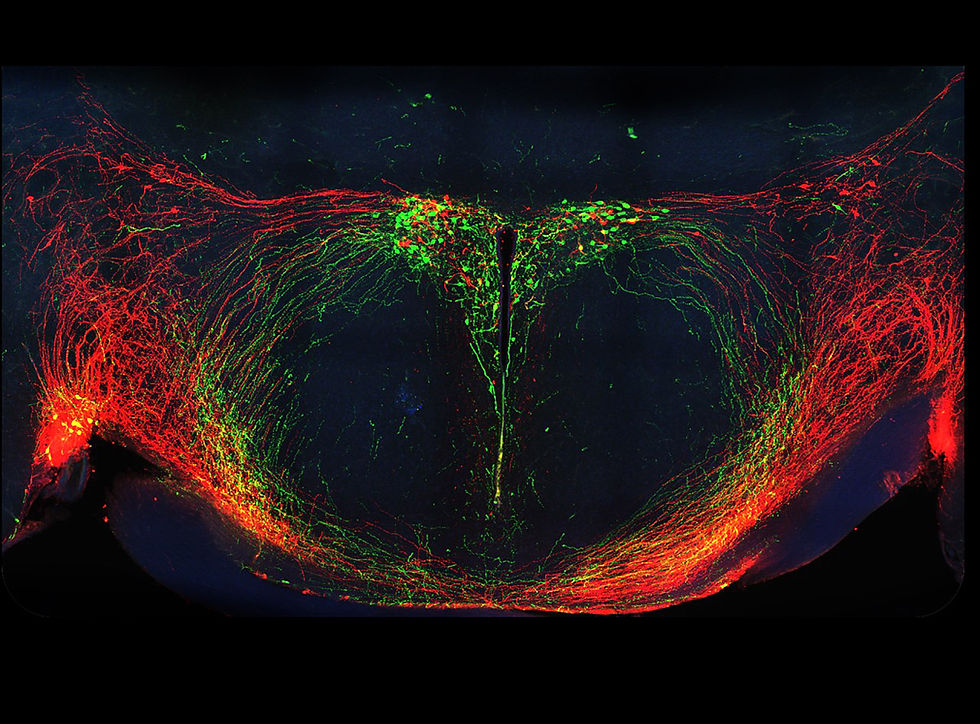

A densely branched network of fine, luminous structures permeates this image. Two color systems are discernible: green and red signaling pathways that partially overlap and bundle together. These are neuronal circuits in the mouse brain through which two important neurotransmitters are distributed: Green denotes oxytocin pathways, red vasopressin networks.

Colloquially known as the "cuddle hormone," oxytocin, among other things, ensures that we feel emotionally connected to other people, build trust, and experience social closeness as pleasant. The close bond between mother and child is also influenced by this hormone.

Oxytocin: Slow, but More Widely Distributed

Normally, the release of neurotransmitters occurs quickly and precisely, primarily via the axons, the longer extensions of nerve cells. Neurons transmit their signals to other cells via these axons. However, oxytocin is different: it can be released directly from the cell body and the extensions of nerve cells, the so-called dendrites. This release from the cell body and dendrites is slower and has a broader effect in the brain.

However, exactly how this works at the molecular level with oxytocin remained largely unclear for a long time – until now. A research team led by Beatriz Aznar-Escolano from the Miguel Hernández Elche University in Spain has now investigated this in more detail.

"We knew that oxytocin is also released from areas in the brain other than the axon, but we had only a limited understanding of how this process is regulated," explains Aznar-Escolano's colleague Sandra Jurado. "Our work focuses on understanding the mechanisms that enable this slow and sustained release, which likely prepares the brain for social interactions."

Mice become less socially engaged

The change can also be observed in the mice's behavior. In behavioral tests, the mice continued to show social interest in their conspecifics, but their interactions were shorter and less pronounced. "The effects are subtle, but very revealing," explains Jurado. "It's not a complete loss of social ability, but rather a fine-tuning of the quality of social interactions."

According to the researchers, this suggests that this slower release pathway of oxytocin maintains a baseline level of the "cuddle hormone." "This prepares the brain to respond appropriately to social stimuli," Jurado explains.

The findings thus provide new insights into the regulation of hormonal signals in the brain and could help to better understand psychiatric disorders in which oxytocin plays a role. (Communications Biology, 2026; doi: 10.1038/s42003-025-09442-5)

Source: Miguel Hernández University of Elche