How Our Brain Embeds Memories

- Jan 10

- 3 min read

Neurons Store Memory Content and Context Separately

Neural division of labor:

Our brain doesn't store past experiences and their context together, but rather in two separate groups of brain cells, as an experiment reveals. Only the combination of both creates a complete memory. Content neurons, therefore, store only the information itself, such as an object or a person. Context neurons, on the other hand, only remember the circumstances. This division of labor makes our memory particularly efficient and flexible, as the team reports in "Nature."

Our episodic memory is remarkably comprehensive and precise: It stores knowledge, remembers the appearance of countless people, and can even recall events from our childhood. However, our memory doesn't work like a photo album: Even during the encoding process, feelings, expectations, and internal filtering mechanisms influence what our brain stores long-term and what it doesn't. Furthermore, these memory contents can be subsequently altered and distorted.

Concept neurons – and who else?

But for a memory to be complete, the brain must store the memory content along with its context. Only then can we, for example, remember the same person or object in different situations. "We already know that deep within the brain's memory centers, specific cells, so-called concept neurons, respond to this person, regardless of the environment in which they appear," explains senior author Florian Mormann from the University of Bonn.

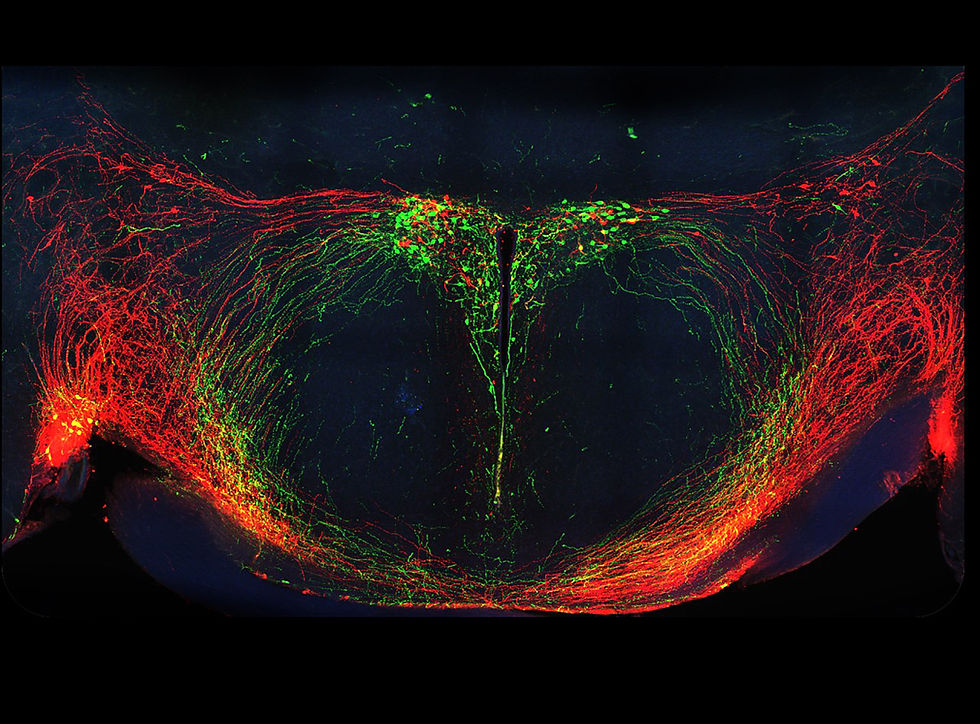

"However, how memory content and context are combined at the neuronal level in humans has remained unclear," write Mormann and his team. In mice, the neurons of the hippocampus store memories along with their context, but this is not the case with human concept neurons. They must therefore collaborate with other brain cells and brain regions to provide memory content with the appropriate context.

Neurons observed during storage

"We therefore asked ourselves: Does our brain represent content and context separately to enable a more flexible memory? And how do these separate pieces of information connect when we need to remember certain content according to the context?" says first author Marcel Bausch from the University of Bonn. To answer these questions, he and his colleagues analyzed the activity of individual neurons in the brains of 16 epilepsy patients. Electrodes were implanted in the hippocampus and surrounding brain regions to improve diagnosis and surgical preparation.

The researchers used this to analyze brain activity during episodic memory in greater detail. The patients were shown pairs of images, which they had to compare based on different questions. For example, they had to decide whether an object appearing in both images differed in size. "This allowed us to observe how the brain processes the exact same image in different task contexts," says Mormann.

Two groups of neurons for one memory

The analysis revealed that two largely separate groups of neurons fired in the test subjects' brains while they viewed the images. One group of brain cells, dubbed content neurons, reacted to specific images regardless of the task or context. The second group, the context neurons, were activated in specific task contexts—regardless of the image or object shown.

“This division of labor likely explains the flexibility of human memory. The brain can reuse the same concept in countless new situations without needing a specialized neuron for each combination by storing content and context in separate ‘neural libraries,’” says Bausch. Mormann adds: “The ability of these groups of nerve cells to spontaneously connect allows us to generalize information while preserving the specific details of individual events.”

Nature, 2026; doi: 10.1038/s41586-025-09910-2)

Source: University of Bonn